AngloSaxon & Celtic Orthodoxy

Anglo-Saxon & Celtic Orthodoxy is about the Orthodoxy of The British Isles, Low Countries and parts of France, Scandinavia in the first millennium and how it might be developed now.

"The Church in The British Isles will only begin to grow when She begins to again venerate Her own Saints" (Saint Arsenios of Paros †1877)

Harold II the last Orthodox king of England.

On October 14, 1066, at Hastings in southern England, the last Orthodox king of England, Harold II, died in battle against Duke William of Normandy. William had been blessed to invade England by the Roman Pope Alexander in order to bring the English Church into full communion with the “reformed Papacy”; for since 1052 the English archbishop had been... banned and denounced as schismatic by Rome. The result of the Norman Conquest was that the English Church and people were integrated into the heretical “Church” of Western, Papist Christendom, which had just, in 1054, fallen away from communion with the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church, represented by the Eastern Patriarchates of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem. Thus ended the nearly five-hundred-year history of the Anglo-Saxon Orthodox Church, which was followed by the demise of the still older Celtic Orthodox Churches in Wales, Scotland and Ireland.

The Orthodox Faith, as it existed from circa A.D. 37 to the Great Schism of A.D. 1054 -The Church of Wales, England, Scotland, Cornwall, Brittany and Ireland in the first Millennium of Christianity

When our Lord Jesus Christ founded the Church, He commanded His Disciples to take the Gospel to the very ends of the earth. Within just a few decades the Church had spread to the British Isles and was soon formally established amongst the peoples of Britain.

THE FIRST THREE THOUSAND YEARS

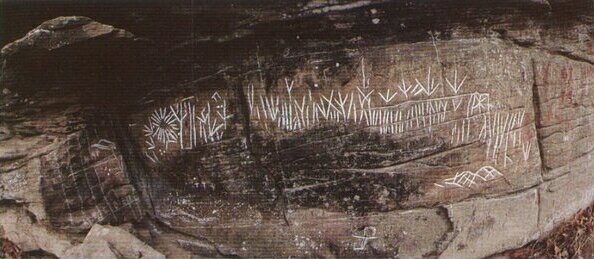

We now know that the British Isles have been regularly populated by an relatively advanced, organised society for between six and seven thousand years. The archaeological evidence of sites such as Cadbury Castle in Somerset shows continuous occupation by advanced, settled people from around 3250BC to AD1060. At the beginning of the period, the land was inhabited by a race often erroneously referred to in earlier text books as the ”Iberians”. These people had an organised religion, which they held in common with their contemporaries in ancient Gaul. Their religion caused them to be considerable builders, yielding such massive structures as Avebury and the lesser Stonehenge built around 4700BC, as well as many others.

The later Celts apparently migrated in two fairly distinct waves, possibly beginning about 700-500BC, apparently absorbing rather than conquering the earlier inhabitants in the process. The first wave was the Goidels (Gaels), who were followed by the Britons.

The incoming Celts appear to have held the religion of the native people, which was druidism. Druidism taught an eternal life after death, the transmigration of souls, a supreme (trinitarian) god and a pantheon of lesser gods. The Celts of the British Isles were at the western end of the "Celtic Crescent" which arched above the Roman Empire from the British Isles (Britain) in the west, through Britony-Galicia in Spain, Bretagne-Gaul in France up to Galicia in southern Poland right across to the last Celtic expansion around 300BC of Galatia in Asia Minor.

ROMAN BRITAIN

The original Roman invasion of Britain began with the arrival of Julius Caesar in 55BC. After ninety years of peace, the Britons again caused trouble and Claudius Caesar sent an army under Plautius to conquer the newly troublesome British in AD43. The Romans never fully conquered the British Isles, it was never really their intention to do so, but merely to secure Gaul. The later part of the Roman rule in Britain can perhaps be characterised as largely peaceful, with Roman and Romano-Briton civilians and retired military sharing the administration as a settled and highly civilized middle-upper class. While the administration was carried out in Latin, the Celtic language remained predominant throughout the country.

THE COMING OF CHRISTIANITY TO THE BRITISH ISLES

In the tradition of the Church, Christianity was brought by people from the region of Ephesus and established in the British Isles by AD45. This is somewhat bolstered by the fact that the Church in the British Isles maintained that its original Liturgy was that of Saint John, who is known to have lived in Ephesus in his later years. Saint Gildas the Wise (a Welsh monk, pupil of St. Illtyd. + AD512) maintained in his History, that Christianity came to Britain in the last year of Tiberius Caesar i.e: AD37.

It is interesting to note that the antiquity of British Church, was unequivocally affirmed by five Papal councils: The council of Pisa (1409), the council of Constance (1417), the council of Sens (1418), the council of Sienna (1424), and the council of Basle (1434). These five councils ruled that the Church in the British Isles is the oldest Church in the gentile world - this despite the fact it would have been politically advantageous for the popes to have ignored the fact, given the possibility of thereby offending France and Spain which were at the time, far more powerful than England. It seems reasonable therefore, to assume that the documentary evidence in favour of the antiquity of the Church in the British Isles must have been overwhelming. Sadly, much of that evidence is now lost, destroyed during Henry VIII's dissolution of the monasteries and the dispersion/destruction of their libraries then, and during the Civil War.

Saint Aristibule (Aristobulus, one of the Seventy Apostles mentioned in the Gospel of Saint Luke 10:1) who died circa AD90, as Bishop of Britain, was one of the early organisers of Christianity among the Celts in Britony and Britain, according to Saint Dorotheus of Tyre. The Orthodox Church regards him as the “Apostle of Britain” and accords him that title. It is to him (and others with him) that we attribute the beginnings of The Church in the British Isles circa AD 37-45.

Recent archaeology suggests the oldest church building remains so far positively identified as such in Britain, as dating from approximately AD140. We also know of domestic Christian remains of earlier date in the south of Britain. Later we have the record of the ruler of part of south Wales-Western England, Saint Lucan bringing Saint Dyfan (often Latinised as Damian) and Saint Fagan (often Latinised as Fugatius) to his area circa AD160-180. Then we have Saint Mydwyn and the Bishop, Saint Elvan, both of whom were Britons, of exactly the same period. Bishop Elvan reputedly died at Glastonbury circa AD195.

The Roman historian Tertullian, in a tract written circa AD208 mentions the Church in Britain as having reached parts as yet unconquered by the Roman Army, which tells us that the Church had moved beyond the Roman pale and was certainly indigenised, as the actions of Saint Lucan clearly show. Origen, writing thirty years later, also records the Church in Britain.

Saint Dyfan (+AD190c) is regarded as the first Christian Martyr of the British Isles (and hence the name of the town of Merthyr Dyfan just south of Cardiff in Wales). The first recorded Christian Martyrs in England were the layman Saint Alban, Bishop Stephen of London, Bishop Socrates of York, Bishop Argulius of London, Bishop Amphibalus of LLandaff, Bishop Nicolas of Penrhyn, Bishop Melior of Carlisle, and others during the period AD300-304.

Constantine, the son of Constantius I (Chlorus) and Flavius Helena (said by Saint Ambrose to have been an innkeeper and by Chesterton and later historians to have possibly been a Briton) accompanied his father from Boulogne to York. There, in AD306 his father died and Constantine was proclaimed Augustus - ruler of the Roman Empire - at York. Eventually he was to become known to posterity as the Emperor Constantine the Great. Constantine together with Licenius issued the so-called Edict of Milan recognising Christianity.

In 314 the Bishop of Eborius (York), Bishop Restitutus of London and Bishop Adelfius of Caerleon and a large retinue attended the Council of Arles.

Saint Athanasius specifically states that the British Church recorded her agreement to the decisions of the First Ecumenical Council held at Nicaea in 325.

Again, in 359, British Bishops attended the Council of Rimini. The archaeological evidence of this period points to the chapels at Lullingstone and Silchester as dating from about 345.

In short, the Church was not only quite well established over much of the British Isles by this time, but we have Saint John Chrysostom himself, testifying that it was fully Orthodox in its doctrine. (Chrysostomi Orat.’O Qeos Cristos)

Very soon after the importation of monasticism from Egypt to the Eastern Empire, it appeared in the British Church and quickly became extremely popular. In fact, the British Church in the fifth century and thereafter, was organised on heavily monastic lines, to a far greater extent perhaps than other parts of the Church. Hundreds of monasteries and hermitages, great and small, spread out across the British Isles. The monastic life appealed to the mystical bent of the Celtic mind.

THE DEPARTURE OF ROME

During the fourth century, eastern Britain began to be subjected to raids from Saxon pirates. Rome found herself defending Gaul and the centre of the Roman Empire from northern invaders. She could no longer attend to the provinces of Britain, and when Alaric sacked Rome in AD410, the flow of soldiers and administrators to Britain ceased entirely. The majority of Britain now devolved to regional government very much according to the particular Clan Chief or “King”.

THE THREE DUKES

This brings us to a period that might conveniently be described as the period of the Three Dukes (Dux Bellorum), or Generals (who may have held the Celtic title of Pendragon) who led the armies of various combinations of Celtic Clans. The first of these was Vortigern who operated from central Wales and Gloucester from about 425 until 457. Duke Vortigern was followed by Duke Emrys. The chronicler Saint Gildas records that he led the armies from 460 to the mid 480s. Arthur appears to have taken the position around the mid-late 480s. The chronicler-Priest Nennus records that Arthur wore an Icon of Saint Mary at the Battle of Bassas and an Icon of the Crucifixion for the whole of the three days of the Battle of Mount Badon (Liddington Castle) in 516.

During the period of the Three Dukes, the Church benefited enormously from the relative civil security. In Emrys’ time, Saint Germanus, Bishop of Auxerre visited Britain twice, advising the British Bishops in setting up schools for Ordinands, and securing the banishment of the few remaining Pelagian heretics. He led a Christian army in an apparently bloodless victory against the combined Picts and Saxons in the north in 431c. He is recorded as preaching very effectively at Glastonbury during his second visit in 447. From this time the monasteries largely ran the government of the Church.

THE MONASTIC CHURCH

In 397 Saint Ninian founded the monastery at Whitehorn in Galloway and began preaching among the Picts and the Scots. This, together with numerous smaller cells of hermits and semi-coenobitic monastics, marked the beginnings of a renewal in the life of the Church in the British Isles.

During this period, the Church government was largely carried out from rural monasteries, where the Abbot ruled the Church. He might (in a great monastery) have several choir-bishops, consecrated because of recognition of their sanctity of life. The Bishop Ordained, Chrismated and Consecrated, while the Abbot administered. Fairly soon, the positions of Abbot and Ruling Bishop began to be combined. Overall the prevailing atmosphere was that of the sanctity of numerous monastic bishops, abbots and hermits. The monasteries were the administrative, educational and missionary centres of the Church. It was from these great monastic centres that the Church in the British Isles later in the first millennium, sent out her renowned monks as far as Germany, Kiev and Scandinavia. Some idea of the calibre of the Church leaders at this time may be gained from the following few representatives.

Around the year 400, the Deacon Calporans of (modern) Cumberland, himself the son of a Priest, had a son, Patrick. About 410, Patrick was kidnapped by raiding Irish pirates and taken to Ireland as a slave. After some six years, he escaped to Gaul where he entered a monastery and was trained to the priesthood. He returned to his family near the Solway of Firth around 426 and was Consecrated Bishop in 432 when he took up residence in Ireland. Saint Patrick ruled as monk-Bishop of Armagh for the next thirty years, founding many monasteries and building up the Church in Ireland until the time of his death in 464.

By AD450-500 there were some great 1,000-1,500 member monasteries in Wales and the west. The Church in the British Isles at this time tended to look to the Patriarchate of Jerusalem as the centre of the Church, as it was largely cut off from the Roman Church (insofar as it was ever connected). While the doctrine of the British Church is well attested to as being entirely Orthodox (The Pelagian heresy never gained more than a passing popularity in Britain and was apparently completely eradicated by the 420s-430s) the system of Church government and general atmosphere differed considerably from that of the Roman Church.

Born just after the turn of the century, Illtyd became a courtier and minister in Wales. He abandoned that life and joined the monastery at Llancarvan under the guidance of its abbot, Saint Cadoc. Later Saint Illtyd left Llancarvan and went to lead the great monastery of Llantwit (Llanilltyd) known subsequently as the house of saints because it produced so many leaders of the Church. Saint Illtyd reposed in 470 and is commemorated on the 6th of November.

Saint David (Dewi Sant) was born early in the fifth century, educated at Hen Vynyw and trained for the Priesthood for ten years under Paulinus the scribe. He founded the extremely ascetic monastery of Menevia. Saint David as Abbot was noted for his works of mercy, extreme asceticism and habit of numerous prostrations. The Synod of Brevi elected him Archbishop and his see was set at Menevia (St. David’s).

History tells us that some of the most powerful leaders of the British Church (Saint David, Archbishop of Menevia, Saint Padarn, Bishop of Avranches and Saint Teilo later Archbishop of Menevia) did obeisance to the Patriarch of Jerusalem in apparently deliberate preference to any other Church leader. It is possible that some were actually consecrated by the Patriarch of Jerusalem. To the Celtic mind, the centre of the Church was the place where Jesus had actually ministered. Saint David is said to have travelled to other Celtic lands and we have records of his presence in Cornwall and in Brittany in 547-48 - he was enormously influential throughout the British Isles and was responsible for much consolidation of the Church and for holding both the clergy and laity to tight discipline. Saint David reposed in 601, his feast is the national day of Wales, the first of March.

Saint Columcille was born in 521 at Gartan. He travelled with some monks to Iona in Scotland where he founded the famous monastery at Iona on an island off the Atlantic coast. There he lived, alternating between the hermit’s cell and ruling the Abbey; sending out his monks to preach among the people. From his successor Abbot, Saint Adamnan, we have a biography which tells graphically of a tall man of very forceful personality, who performed miracles during his lifetime.

Columcille built the Monastery of Iona and set up subsidiary monasteries in Hinba, Maglunge and Diuni. Three surviving poems are ascribed to him including Altus Prosator which concerns the after-life and final judgement. He took great care with the training of the monks, some of whom were converts from among the Anglo-Saxon invaders of eastern Britain. He converted Bude, king of the Picts, and in 574, he crowned King Aiden of Dalriada. Columcille was a Bishop of great influence in Scotland and Ireland as well as the whole north of England until his death in the church just before Mattins on the 9th of June, 597.

THE RETREAT OF THE CELTS AND RISE OF THE SAXON EAST

After the Battle of Mount Badon, the Britons could no longer hold their ground. The Saxons increasingly migrated from Europe, filling the Saxon Shore and pressing westward. They established a number of heathen kingdoms in the south-east, east and north-east of what is now England.

THE ROMAN MISSION

In AD597 the Patriarchate of Rome decided to mount what can only be described as an ecclesiastical invasion of the British Isles. This came in the form of an uninvited “mission” established by Saint Augustine at Canterbury in spite of the fact that he found Bishop Liuthard and the church of Saint Martin already there at Canterbury. Bishop Liuthard was close to the court of King Ethelbert who was not himself a Christian, but Queen Bertha was. Undaunted by the existence of the long-established Church in the British Isles, Augustine proceeded to work among the non-Christian Saxon invaders living in Kent.

Claims that Augustine was Primate of Britain are spurious, given that the Church in the British Isles already had its own Primate - the successor to Saint David, (who had died some 20 years before Augustine's arrival). The Church in the British Isles had approximately 120 bishops and many thousands of priests, monks and nuns. Augustine tried to assert Pope Gregory the Great's authority, but his efforts were not in any great degree successful beyond the south-eastern corner of the island where he worked to convert the invader Saxons.

To resolve some differences between the Church in the British Isles and the invading Roman mission, a council was held in 664 at Whitby in Yorkshire, resulting in the Celtic Church and the Roman “mission” being formally amalgamated into one Church, albeit the Celtic party resumed their own customs in their part of Britain. Because this joining was concurrent with the large-scale conversion of the Anglo- Saxon invaders of eastern England, this continuing Church was Celtic-Anglo-Saxon in makeup and began to take on a character of both races. It was an integral part of the Orthodox Catholic Church, and, since the Papacy at that time had hardly begun to develop in the sense that we now know it, this Church of the British Isles remained a Local Church within the world wide Orthodox Catholic Church.

In the year 666, Saint Theodore of Tarsus, a Greek monk was appointed to the See of Canterbury. He arrived in 669 at the age of 67 and began a twenty year episcopate of trying to persuade the British Bishops to accept him as Archbishop. Theodore was opposed by Rome in some of his decisions, most obviously in his disputes with Saint Wilfrid. In the end, while he did much to organise the Church in the British Isles, so divided by the Synod of Whitby, his power extended really only to the Anglo-Saxon part of the country. Theodore initiated the series of Holy Synods, starting with Hertford in 672 at which the famous ten decrees were passed, paralleling the canons of the Council of Chalcedon. The second Synod at Hatfield produced a statement of orthodoxy regarding the monothelite controversy.

At the end of the Seventh Century, (Saint) Wilfrid, now the Bishop of York, asked the Patriarch of Rome to intervene in his quarrel with (Saint) Theodore, the Archbishop of Canterbury. When the matter came up before the Witenagamot - the Royal Parliament, the members - Aldermen, Thegnes and Bishops - rejected the Pope's adjudication. The Witenagamot said, in effect, "Who is this Pope and what are his decrees? What have they to do with us, or we with them?" By way of an answer they burned the Papal parchment and put Wilfrid in prison for having the temerity appeal to an outsider.

In A.D. 747, the principle was reasserted again - and just as pointedly. It was proposed at the Witenagamot to refer difficult questions to the Bishop of Rome - as primus inter pares, first among equals. The Witenagamot, however, declared it would submit only to the jurisdiction of the British Archbishop.

THE HEPTARCHY AND BEYOND

The period of the so-called “Heptarchy” extended roughly from 600 to around 850 and owes its name to the prominence of the new Saxon kingdoms of Kent, Wessex, Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Essex and Sussex of what is now England. This was not a politically stable period, with the continuation of a struggle for supremacy between these kingdoms aided by whatever allies they could marshal. At the outset of the period, Kent was overlord of Essex and Sussex and arguably the most powerful kingdom in Britain. However, during the sixth century, Northumbria began to take the lead. Northumbria consisted of two parts including most of modern Yorkshire. Under King Edwin, it incorporated the Saxon kingdom of Berenice, which started out not being Christian. However it was soon converted. At its northern edge Edwin built Edwin’s Burgh on the Firth of Forth (Edinburgh).

Edwin was killed in battle with the combined armies of the heathen kingdom of Mercia and the Christian Kingdom of Wales in 632. The brothers Oswald and Oswy had, during Edwin’s rule, lived in the Monastery at Iona. Upon Edwin’s death, Oswald led an army of Northumbria against the Anglo-Saxons and became King of Northumbria. In 634 Saint Aidan, at King Oswald’s invitation, came from the Monastery at Iona, to set up his See at Lindisfarne, as Bishop of all of Northumbria. Here he founded his monastery, staffed by a group of monks who had accompanied him from Iona. Oswald was killed in battle 642 and was subsequently canonised by the Church.

THE BEGINNINGS OF NATIONAL UNITY OF ENGLAND

Before his death, King Penda admitted Saint Aidan’s missionary monks to Mercia, thus paving the way for the conversion of this Saxon kingdom. His son was Baptised and married a Christian Princess. For most of the next century the Kingdom of Mercia, with its territory running south from the Humber to the Thames and from the Welsh Borders to the Wash was in the ascendant. Mercia’s supremacy culminated in the reign of his cousin, King Offa (757-96).

King Offa is regarded as the first King to be termed King of all England. He dealt with his younger European contemporary, the Emperor Charlemagne as an equal, signing a commercial treaty with him in 796, while Charlemagne is recorded as having regarded him as an outstanding ruler.

In 850-851 the heathen Danish raiders, who had for some time contented themselves with summer raids, decided to winter on the Isle of Thanet. This was in effect the beginning of the terrible Danish invasion which was to provide the Church with so many martyrs, especially in the year 870.

King Alfred eventually defeated the Danes and consolidated his rule, maintaining peace until the Danes attacked from France again in 892. He finally directed their defeat in 896-7.

Both Offa and Alfred were law-makers, scholars in their own right, Christian Kings, who built a school system and generally encouraged learning and the extension of the Church.

The Orthodoxy of the Church in the British Isles ceased with the introduction of papal bishops after the Battle of Hastings in October of 1066 at which the Norman Duke William, funded by the newly schismatic papacy invaded Britain.

*************************************

As early as the 7th century, Celtic Crosses were erected in regions of Ireland and Great Britain as testaments to the Christian faith.

The Celtic Cross is symbolic of Celtic Christianity. It is a characteristic symbol combining a cross with a ring that surrounds the intersection. The Celtic Cross has also been called the Irish Cross, the Cross of Iona and the High Cross. There are still many free standing crosses that have survived the ages scattered throughout Ireland, Wales, in the Hebrides and on the island of Iona. There is an ancient story still alive in Ireland today that the Celtic Cross was founded in Ireland by Saint Patrick. Saint Patrick combined the Cross with the symbol of the sun, giving pagan followers the combined symbol of Christianity with the life-giving symbolism of the sun.

"The Church in The British Isles will only begin to grow when She begins to again venerate Her own Saints" (Saint Arsenios of Paros †1877)

Harold II the last Orthodox king of England.

On October 14, 1066, at Hastings in southern England, the last Orthodox king of England, Harold II, died in battle against Duke William of Normandy. William had been blessed to invade England by the Roman Pope Alexander in order to bring the English Church into full communion with the “reformed Papacy”; for since 1052 the English archbishop had been... banned and denounced as schismatic by Rome. The result of the Norman Conquest was that the English Church and people were integrated into the heretical “Church” of Western, Papist Christendom, which had just, in 1054, fallen away from communion with the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church, represented by the Eastern Patriarchates of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem. Thus ended the nearly five-hundred-year history of the Anglo-Saxon Orthodox Church, which was followed by the demise of the still older Celtic Orthodox Churches in Wales, Scotland and Ireland.

The Orthodox Faith, as it existed from circa A.D. 37 to the Great Schism of A.D. 1054 -The Church of Wales, England, Scotland, Cornwall, Brittany and Ireland in the first Millennium of Christianity

When our Lord Jesus Christ founded the Church, He commanded His Disciples to take the Gospel to the very ends of the earth. Within just a few decades the Church had spread to the British Isles and was soon formally established amongst the peoples of Britain.

THE FIRST THREE THOUSAND YEARS

We now know that the British Isles have been regularly populated by an relatively advanced, organised society for between six and seven thousand years. The archaeological evidence of sites such as Cadbury Castle in Somerset shows continuous occupation by advanced, settled people from around 3250BC to AD1060. At the beginning of the period, the land was inhabited by a race often erroneously referred to in earlier text books as the ”Iberians”. These people had an organised religion, which they held in common with their contemporaries in ancient Gaul. Their religion caused them to be considerable builders, yielding such massive structures as Avebury and the lesser Stonehenge built around 4700BC, as well as many others.

The later Celts apparently migrated in two fairly distinct waves, possibly beginning about 700-500BC, apparently absorbing rather than conquering the earlier inhabitants in the process. The first wave was the Goidels (Gaels), who were followed by the Britons.

The incoming Celts appear to have held the religion of the native people, which was druidism. Druidism taught an eternal life after death, the transmigration of souls, a supreme (trinitarian) god and a pantheon of lesser gods. The Celts of the British Isles were at the western end of the "Celtic Crescent" which arched above the Roman Empire from the British Isles (Britain) in the west, through Britony-Galicia in Spain, Bretagne-Gaul in France up to Galicia in southern Poland right across to the last Celtic expansion around 300BC of Galatia in Asia Minor.

ROMAN BRITAIN

The original Roman invasion of Britain began with the arrival of Julius Caesar in 55BC. After ninety years of peace, the Britons again caused trouble and Claudius Caesar sent an army under Plautius to conquer the newly troublesome British in AD43. The Romans never fully conquered the British Isles, it was never really their intention to do so, but merely to secure Gaul. The later part of the Roman rule in Britain can perhaps be characterised as largely peaceful, with Roman and Romano-Briton civilians and retired military sharing the administration as a settled and highly civilized middle-upper class. While the administration was carried out in Latin, the Celtic language remained predominant throughout the country.

THE COMING OF CHRISTIANITY TO THE BRITISH ISLES

In the tradition of the Church, Christianity was brought by people from the region of Ephesus and established in the British Isles by AD45. This is somewhat bolstered by the fact that the Church in the British Isles maintained that its original Liturgy was that of Saint John, who is known to have lived in Ephesus in his later years. Saint Gildas the Wise (a Welsh monk, pupil of St. Illtyd. + AD512) maintained in his History, that Christianity came to Britain in the last year of Tiberius Caesar i.e: AD37.

It is interesting to note that the antiquity of British Church, was unequivocally affirmed by five Papal councils: The council of Pisa (1409), the council of Constance (1417), the council of Sens (1418), the council of Sienna (1424), and the council of Basle (1434). These five councils ruled that the Church in the British Isles is the oldest Church in the gentile world - this despite the fact it would have been politically advantageous for the popes to have ignored the fact, given the possibility of thereby offending France and Spain which were at the time, far more powerful than England. It seems reasonable therefore, to assume that the documentary evidence in favour of the antiquity of the Church in the British Isles must have been overwhelming. Sadly, much of that evidence is now lost, destroyed during Henry VIII's dissolution of the monasteries and the dispersion/destruction of their libraries then, and during the Civil War.

Saint Aristibule (Aristobulus, one of the Seventy Apostles mentioned in the Gospel of Saint Luke 10:1) who died circa AD90, as Bishop of Britain, was one of the early organisers of Christianity among the Celts in Britony and Britain, according to Saint Dorotheus of Tyre. The Orthodox Church regards him as the “Apostle of Britain” and accords him that title. It is to him (and others with him) that we attribute the beginnings of The Church in the British Isles circa AD 37-45.

Recent archaeology suggests the oldest church building remains so far positively identified as such in Britain, as dating from approximately AD140. We also know of domestic Christian remains of earlier date in the south of Britain. Later we have the record of the ruler of part of south Wales-Western England, Saint Lucan bringing Saint Dyfan (often Latinised as Damian) and Saint Fagan (often Latinised as Fugatius) to his area circa AD160-180. Then we have Saint Mydwyn and the Bishop, Saint Elvan, both of whom were Britons, of exactly the same period. Bishop Elvan reputedly died at Glastonbury circa AD195.

The Roman historian Tertullian, in a tract written circa AD208 mentions the Church in Britain as having reached parts as yet unconquered by the Roman Army, which tells us that the Church had moved beyond the Roman pale and was certainly indigenised, as the actions of Saint Lucan clearly show. Origen, writing thirty years later, also records the Church in Britain.

Saint Dyfan (+AD190c) is regarded as the first Christian Martyr of the British Isles (and hence the name of the town of Merthyr Dyfan just south of Cardiff in Wales). The first recorded Christian Martyrs in England were the layman Saint Alban, Bishop Stephen of London, Bishop Socrates of York, Bishop Argulius of London, Bishop Amphibalus of LLandaff, Bishop Nicolas of Penrhyn, Bishop Melior of Carlisle, and others during the period AD300-304.

Constantine, the son of Constantius I (Chlorus) and Flavius Helena (said by Saint Ambrose to have been an innkeeper and by Chesterton and later historians to have possibly been a Briton) accompanied his father from Boulogne to York. There, in AD306 his father died and Constantine was proclaimed Augustus - ruler of the Roman Empire - at York. Eventually he was to become known to posterity as the Emperor Constantine the Great. Constantine together with Licenius issued the so-called Edict of Milan recognising Christianity.

In 314 the Bishop of Eborius (York), Bishop Restitutus of London and Bishop Adelfius of Caerleon and a large retinue attended the Council of Arles.

Saint Athanasius specifically states that the British Church recorded her agreement to the decisions of the First Ecumenical Council held at Nicaea in 325.

Again, in 359, British Bishops attended the Council of Rimini. The archaeological evidence of this period points to the chapels at Lullingstone and Silchester as dating from about 345.

In short, the Church was not only quite well established over much of the British Isles by this time, but we have Saint John Chrysostom himself, testifying that it was fully Orthodox in its doctrine. (Chrysostomi Orat.’O Qeos Cristos)

Very soon after the importation of monasticism from Egypt to the Eastern Empire, it appeared in the British Church and quickly became extremely popular. In fact, the British Church in the fifth century and thereafter, was organised on heavily monastic lines, to a far greater extent perhaps than other parts of the Church. Hundreds of monasteries and hermitages, great and small, spread out across the British Isles. The monastic life appealed to the mystical bent of the Celtic mind.

THE DEPARTURE OF ROME

During the fourth century, eastern Britain began to be subjected to raids from Saxon pirates. Rome found herself defending Gaul and the centre of the Roman Empire from northern invaders. She could no longer attend to the provinces of Britain, and when Alaric sacked Rome in AD410, the flow of soldiers and administrators to Britain ceased entirely. The majority of Britain now devolved to regional government very much according to the particular Clan Chief or “King”.

THE THREE DUKES

This brings us to a period that might conveniently be described as the period of the Three Dukes (Dux Bellorum), or Generals (who may have held the Celtic title of Pendragon) who led the armies of various combinations of Celtic Clans. The first of these was Vortigern who operated from central Wales and Gloucester from about 425 until 457. Duke Vortigern was followed by Duke Emrys. The chronicler Saint Gildas records that he led the armies from 460 to the mid 480s. Arthur appears to have taken the position around the mid-late 480s. The chronicler-Priest Nennus records that Arthur wore an Icon of Saint Mary at the Battle of Bassas and an Icon of the Crucifixion for the whole of the three days of the Battle of Mount Badon (Liddington Castle) in 516.

During the period of the Three Dukes, the Church benefited enormously from the relative civil security. In Emrys’ time, Saint Germanus, Bishop of Auxerre visited Britain twice, advising the British Bishops in setting up schools for Ordinands, and securing the banishment of the few remaining Pelagian heretics. He led a Christian army in an apparently bloodless victory against the combined Picts and Saxons in the north in 431c. He is recorded as preaching very effectively at Glastonbury during his second visit in 447. From this time the monasteries largely ran the government of the Church.

THE MONASTIC CHURCH

In 397 Saint Ninian founded the monastery at Whitehorn in Galloway and began preaching among the Picts and the Scots. This, together with numerous smaller cells of hermits and semi-coenobitic monastics, marked the beginnings of a renewal in the life of the Church in the British Isles.

During this period, the Church government was largely carried out from rural monasteries, where the Abbot ruled the Church. He might (in a great monastery) have several choir-bishops, consecrated because of recognition of their sanctity of life. The Bishop Ordained, Chrismated and Consecrated, while the Abbot administered. Fairly soon, the positions of Abbot and Ruling Bishop began to be combined. Overall the prevailing atmosphere was that of the sanctity of numerous monastic bishops, abbots and hermits. The monasteries were the administrative, educational and missionary centres of the Church. It was from these great monastic centres that the Church in the British Isles later in the first millennium, sent out her renowned monks as far as Germany, Kiev and Scandinavia. Some idea of the calibre of the Church leaders at this time may be gained from the following few representatives.

Around the year 400, the Deacon Calporans of (modern) Cumberland, himself the son of a Priest, had a son, Patrick. About 410, Patrick was kidnapped by raiding Irish pirates and taken to Ireland as a slave. After some six years, he escaped to Gaul where he entered a monastery and was trained to the priesthood. He returned to his family near the Solway of Firth around 426 and was Consecrated Bishop in 432 when he took up residence in Ireland. Saint Patrick ruled as monk-Bishop of Armagh for the next thirty years, founding many monasteries and building up the Church in Ireland until the time of his death in 464.

By AD450-500 there were some great 1,000-1,500 member monasteries in Wales and the west. The Church in the British Isles at this time tended to look to the Patriarchate of Jerusalem as the centre of the Church, as it was largely cut off from the Roman Church (insofar as it was ever connected). While the doctrine of the British Church is well attested to as being entirely Orthodox (The Pelagian heresy never gained more than a passing popularity in Britain and was apparently completely eradicated by the 420s-430s) the system of Church government and general atmosphere differed considerably from that of the Roman Church.

Born just after the turn of the century, Illtyd became a courtier and minister in Wales. He abandoned that life and joined the monastery at Llancarvan under the guidance of its abbot, Saint Cadoc. Later Saint Illtyd left Llancarvan and went to lead the great monastery of Llantwit (Llanilltyd) known subsequently as the house of saints because it produced so many leaders of the Church. Saint Illtyd reposed in 470 and is commemorated on the 6th of November.

Saint David (Dewi Sant) was born early in the fifth century, educated at Hen Vynyw and trained for the Priesthood for ten years under Paulinus the scribe. He founded the extremely ascetic monastery of Menevia. Saint David as Abbot was noted for his works of mercy, extreme asceticism and habit of numerous prostrations. The Synod of Brevi elected him Archbishop and his see was set at Menevia (St. David’s).

History tells us that some of the most powerful leaders of the British Church (Saint David, Archbishop of Menevia, Saint Padarn, Bishop of Avranches and Saint Teilo later Archbishop of Menevia) did obeisance to the Patriarch of Jerusalem in apparently deliberate preference to any other Church leader. It is possible that some were actually consecrated by the Patriarch of Jerusalem. To the Celtic mind, the centre of the Church was the place where Jesus had actually ministered. Saint David is said to have travelled to other Celtic lands and we have records of his presence in Cornwall and in Brittany in 547-48 - he was enormously influential throughout the British Isles and was responsible for much consolidation of the Church and for holding both the clergy and laity to tight discipline. Saint David reposed in 601, his feast is the national day of Wales, the first of March.

Saint Columcille was born in 521 at Gartan. He travelled with some monks to Iona in Scotland where he founded the famous monastery at Iona on an island off the Atlantic coast. There he lived, alternating between the hermit’s cell and ruling the Abbey; sending out his monks to preach among the people. From his successor Abbot, Saint Adamnan, we have a biography which tells graphically of a tall man of very forceful personality, who performed miracles during his lifetime.

Columcille built the Monastery of Iona and set up subsidiary monasteries in Hinba, Maglunge and Diuni. Three surviving poems are ascribed to him including Altus Prosator which concerns the after-life and final judgement. He took great care with the training of the monks, some of whom were converts from among the Anglo-Saxon invaders of eastern Britain. He converted Bude, king of the Picts, and in 574, he crowned King Aiden of Dalriada. Columcille was a Bishop of great influence in Scotland and Ireland as well as the whole north of England until his death in the church just before Mattins on the 9th of June, 597.

THE RETREAT OF THE CELTS AND RISE OF THE SAXON EAST

After the Battle of Mount Badon, the Britons could no longer hold their ground. The Saxons increasingly migrated from Europe, filling the Saxon Shore and pressing westward. They established a number of heathen kingdoms in the south-east, east and north-east of what is now England.

THE ROMAN MISSION

In AD597 the Patriarchate of Rome decided to mount what can only be described as an ecclesiastical invasion of the British Isles. This came in the form of an uninvited “mission” established by Saint Augustine at Canterbury in spite of the fact that he found Bishop Liuthard and the church of Saint Martin already there at Canterbury. Bishop Liuthard was close to the court of King Ethelbert who was not himself a Christian, but Queen Bertha was. Undaunted by the existence of the long-established Church in the British Isles, Augustine proceeded to work among the non-Christian Saxon invaders living in Kent.

Claims that Augustine was Primate of Britain are spurious, given that the Church in the British Isles already had its own Primate - the successor to Saint David, (who had died some 20 years before Augustine's arrival). The Church in the British Isles had approximately 120 bishops and many thousands of priests, monks and nuns. Augustine tried to assert Pope Gregory the Great's authority, but his efforts were not in any great degree successful beyond the south-eastern corner of the island where he worked to convert the invader Saxons.

To resolve some differences between the Church in the British Isles and the invading Roman mission, a council was held in 664 at Whitby in Yorkshire, resulting in the Celtic Church and the Roman “mission” being formally amalgamated into one Church, albeit the Celtic party resumed their own customs in their part of Britain. Because this joining was concurrent with the large-scale conversion of the Anglo- Saxon invaders of eastern England, this continuing Church was Celtic-Anglo-Saxon in makeup and began to take on a character of both races. It was an integral part of the Orthodox Catholic Church, and, since the Papacy at that time had hardly begun to develop in the sense that we now know it, this Church of the British Isles remained a Local Church within the world wide Orthodox Catholic Church.

In the year 666, Saint Theodore of Tarsus, a Greek monk was appointed to the See of Canterbury. He arrived in 669 at the age of 67 and began a twenty year episcopate of trying to persuade the British Bishops to accept him as Archbishop. Theodore was opposed by Rome in some of his decisions, most obviously in his disputes with Saint Wilfrid. In the end, while he did much to organise the Church in the British Isles, so divided by the Synod of Whitby, his power extended really only to the Anglo-Saxon part of the country. Theodore initiated the series of Holy Synods, starting with Hertford in 672 at which the famous ten decrees were passed, paralleling the canons of the Council of Chalcedon. The second Synod at Hatfield produced a statement of orthodoxy regarding the monothelite controversy.

At the end of the Seventh Century, (Saint) Wilfrid, now the Bishop of York, asked the Patriarch of Rome to intervene in his quarrel with (Saint) Theodore, the Archbishop of Canterbury. When the matter came up before the Witenagamot - the Royal Parliament, the members - Aldermen, Thegnes and Bishops - rejected the Pope's adjudication. The Witenagamot said, in effect, "Who is this Pope and what are his decrees? What have they to do with us, or we with them?" By way of an answer they burned the Papal parchment and put Wilfrid in prison for having the temerity appeal to an outsider.

In A.D. 747, the principle was reasserted again - and just as pointedly. It was proposed at the Witenagamot to refer difficult questions to the Bishop of Rome - as primus inter pares, first among equals. The Witenagamot, however, declared it would submit only to the jurisdiction of the British Archbishop.

THE HEPTARCHY AND BEYOND

The period of the so-called “Heptarchy” extended roughly from 600 to around 850 and owes its name to the prominence of the new Saxon kingdoms of Kent, Wessex, Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Essex and Sussex of what is now England. This was not a politically stable period, with the continuation of a struggle for supremacy between these kingdoms aided by whatever allies they could marshal. At the outset of the period, Kent was overlord of Essex and Sussex and arguably the most powerful kingdom in Britain. However, during the sixth century, Northumbria began to take the lead. Northumbria consisted of two parts including most of modern Yorkshire. Under King Edwin, it incorporated the Saxon kingdom of Berenice, which started out not being Christian. However it was soon converted. At its northern edge Edwin built Edwin’s Burgh on the Firth of Forth (Edinburgh).

Edwin was killed in battle with the combined armies of the heathen kingdom of Mercia and the Christian Kingdom of Wales in 632. The brothers Oswald and Oswy had, during Edwin’s rule, lived in the Monastery at Iona. Upon Edwin’s death, Oswald led an army of Northumbria against the Anglo-Saxons and became King of Northumbria. In 634 Saint Aidan, at King Oswald’s invitation, came from the Monastery at Iona, to set up his See at Lindisfarne, as Bishop of all of Northumbria. Here he founded his monastery, staffed by a group of monks who had accompanied him from Iona. Oswald was killed in battle 642 and was subsequently canonised by the Church.

THE BEGINNINGS OF NATIONAL UNITY OF ENGLAND

Before his death, King Penda admitted Saint Aidan’s missionary monks to Mercia, thus paving the way for the conversion of this Saxon kingdom. His son was Baptised and married a Christian Princess. For most of the next century the Kingdom of Mercia, with its territory running south from the Humber to the Thames and from the Welsh Borders to the Wash was in the ascendant. Mercia’s supremacy culminated in the reign of his cousin, King Offa (757-96).

King Offa is regarded as the first King to be termed King of all England. He dealt with his younger European contemporary, the Emperor Charlemagne as an equal, signing a commercial treaty with him in 796, while Charlemagne is recorded as having regarded him as an outstanding ruler.

In 850-851 the heathen Danish raiders, who had for some time contented themselves with summer raids, decided to winter on the Isle of Thanet. This was in effect the beginning of the terrible Danish invasion which was to provide the Church with so many martyrs, especially in the year 870.

King Alfred eventually defeated the Danes and consolidated his rule, maintaining peace until the Danes attacked from France again in 892. He finally directed their defeat in 896-7.

Both Offa and Alfred were law-makers, scholars in their own right, Christian Kings, who built a school system and generally encouraged learning and the extension of the Church.

The Orthodoxy of the Church in the British Isles ceased with the introduction of papal bishops after the Battle of Hastings in October of 1066 at which the Norman Duke William, funded by the newly schismatic papacy invaded Britain.

*************************************

As early as the 7th century, Celtic Crosses were erected in regions of Ireland and Great Britain as testaments to the Christian faith.

The Celtic Cross is symbolic of Celtic Christianity. It is a characteristic symbol combining a cross with a ring that surrounds the intersection. The Celtic Cross has also been called the Irish Cross, the Cross of Iona and the High Cross. There are still many free standing crosses that have survived the ages scattered throughout Ireland, Wales, in the Hebrides and on the island of Iona. There is an ancient story still alive in Ireland today that the Celtic Cross was founded in Ireland by Saint Patrick. Saint Patrick combined the Cross with the symbol of the sun, giving pagan followers the combined symbol of Christianity with the life-giving symbolism of the sun.